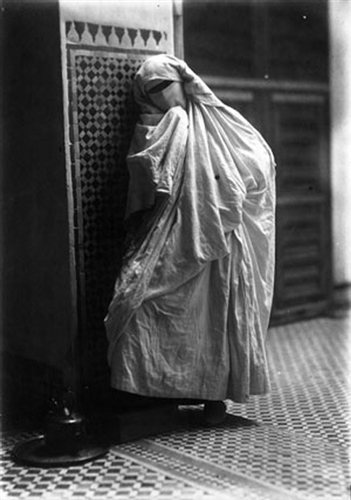

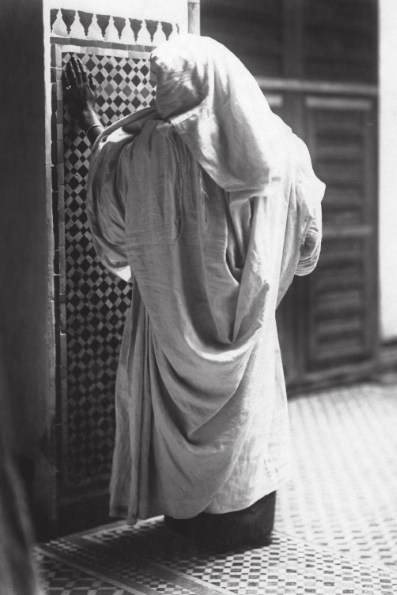

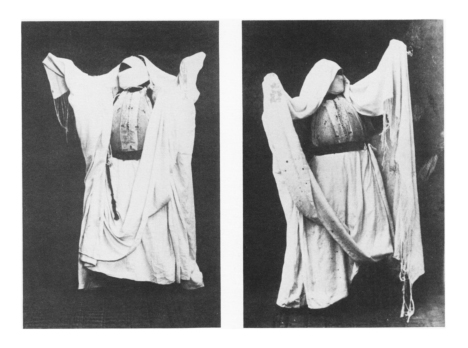

© Gaëtan Gatian de Clerambault, photographs

© Gaëtan Gatian de Clerambault, photographs

taken between 1914 and 1918, while C was in Morocco recuperating from a war wound.

“…consider the relation of this figure to the photographs taken by Clerambault. Does this historical fantasy of colonial cloth underlie his photographs? Do we see in them not, as some of them seemed earlier to suggest, a cloth defined by its utility but rather by the way it curtains off an inaccessible pleasure? There is some reason to believe that this is so, for we discover in Clerambault’s work the rudiments of just such a fantasy. Cloth was of interest to Clerambault not only as an ethnographic issue, but also as a clinical one: for in the course of his psychiatric studies, he noticed that several of his women patients expressed a peculiar passion for cloth. On the basis of these observations, he isolated this passion as a definable clinical entity: a specifically female perversion that resembled, in many respects, the male perversion of fetishism. Clerambault wrote very confidently, however, about why the two perversions ought not to be collapsed, stating the fundamental distinction thus: while for the male, fetishism represents an “homage to the opposite sex,” and thus puts into play an entire fantasy of love, of union with the opposite sex, the perverse female passion for cloth is rooted in the very refusal of this fantasy. The dream of union, of shared love, plays no role either in the genesis or in the sustaining of the perversion. “With no more reverie than a solitary gourmet savoring a delicate wine,”52 the woman enjoys the cloth-for itself, not for any imagined connection it might have with the opposite sex, not because it has any existential or symbolic relation to a male object of desire.

In other words, Clerambault conceived the female passion for cloth as selfish. The perversion that simply uses cloth to obtain orgasmic pleasure is seen as useless in terms of its ability to secure the common happiness of men and women. It is for this reason that Clerambault refers to the perversion as an asexual fetishism; what is missing from it is the sexual relation.

Is this not, mutatis mutandis, a clinical version of the colonialist fantasy of a cloth that acted as barrier to union? Is this symptom not the exception, the surplus sexuality that makes the utilitarian dream of reciprocal relations possible? And are we not, then, presented with this very fantasy in Clerambault’s photographs? My brief answer is: yes and no. Although this fantasy does indeed provide the historical basis of the photographs, we find in them, I would argue, not only another version of the fantasy, but additionally and precisely a perversion of it. For these 40,000 photographs focused on one rigidly adhered to object-choice -cloth -betray not simply a fantasy of cloth, but a fetishization of it. But how is such a distinction to be drawn?

Freud formulated an exact, if too concise, definition of the difference between neurosis and perversion: neurosis, he said, is the negative S of perversion. It is perhaps this definition that Lacan had in mind when he distinguished neurotic fantasy and perversion thus: perversion, he said, is “an inverted effect of the phantasy. [In perversion] the subject determines himself as object in his encounter with the division of subjectivity.”

excerpt of The Sartorial Superego by Joan Copjec. Source: October, Vol. 50 (Autumn, 1989), pp. 56-95

One thought on “┐ Gaëtan Gatian de Clerambault └”