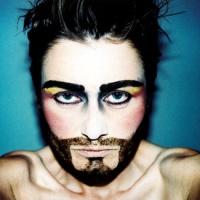

© Sanne Sannes, The face of love, 1965

© Sanne Sannes, The face of love, 1965

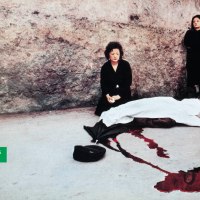

© Sanne Sannes, Untitled, 1962-65

© Sanne Sannes, Untitled, 1962-65

Can love restore the ‘primitive-ego’? is obviously not a question I have the answer for but, nonetheless, it is one that is worth revisiting now and then. It’s not difficult to understand that ‘falling in love’ is an event that messes with the boundaries of the ego. However, it’s not as easier to grasp what exactly happens to us when a lover alternates between subject and object. In Civilization and its Discontents (1929), Freud argues that there is only one state (non-pathological) where the ego seizes to keep itself clearly and sharply outlined and delimited. Freud is referring to the state of ‘being in love’, to which he adds that: Against all the evidence of his senses, the man in love declares that he and his beloved are one, and is prepared to behave as if it were a fact.

Having a sense of one’s own ego means that, somehow, one manages to distinguish between internal and external stimuli. A construction of an ego also implies the recognizance of things existing in the external world as objects, as well as the abidance to the pleasure-principal, meaning to avoid events and things that might cause harm or pain. What interests me is this freudian idea that the primitive pleasure-ego gives way to a more mature ego because it ‘succumbs’ to the reality-principle:

Originally the ego includes everything, later it detaches from itself the external world. The ego-feeling we are aware of now is thus only a shrunken vestige of a far more extensive feeling – a feeling which embraced the universe and expressed an inseparable connection of the ego with the external world. If we may suppose that this primary ego-feeling has been preserved in the minds of many people – to a greater or lesser extent – it would co-exist like a sort of counterpart with the narrower and more sharply outlined ego-feeling of maturity, and the ideational content belonging to it would be precisely the notion of limitless extension and oneness with the universe. (Freud)

Freud then goes on to explain that when faced with the question of ‘what does a man demands of life’ – the answer being happiness -, one easily comprehends that there is a deep struggle at the core of our being, since we live by the pleasure-principle and we desire to experience intense satisfaction but the ways through which we attain pleasure are often criticized/outlawed by society.

If we accept the notion that love is, today, a kind of healthy way to restore the ego, i.e., to restore its harmony with the external world, opening a whole new sort of possibilities; and if love, sexual love, gives us our most intense experience of an overwhelming pleasurable sensation, then, Freud asks, why abandon this path for happiness? The answer being: We are never so defenceless against suffering as when we love, never so forlornly unhappy as when we have lost our love-object or its love.

Though it may seem over-simplified, Freud argues that it’s this genuine search for happiness that drives humanity to center its life around ‘genital love‘. The problem arises when one reflects upon what this does for the ego, since such a subject leads a life that is very dependent on an external object – the object of love. But this isn’t the only reason for shortening the experience of ‘sexual love’, for love opposes the interests of culture; on the other, culture menaces love with grievous restrictions.[…] culture obeys the laws of psychological economic necessity in making the restrictions, for it obtains a great part of the mental energy it needs by subtracting it from sexuality.

A lot more could be said about the restrictions imposed by the so-called civilized societies upon the sexual behaviors that fulfill the pleasure-principle. Overall, this is just illustrates the process of evolution that served the reality principle and the functioning of an organized and capitalist society at the expense of human happiness. If when a love-relationship is at its height, no room is left for any interest in the surrounding world; what would happen to society if, in fact, it valued the time needed to love?