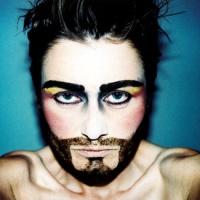

caption: Oliviero Toscani for Benetton, 1992. In 1982 the Mafia killing of Benedetto Grado in Palermo, Italy, was captured by Franco Zecchi. Ten years later the image was featured in Benetton’s spring/summer 1992 campaign. Various publications refused to publish the image and the dead man’s daughter claimed she would sue, asking: “How does my father’s death enter into publicity for sweaters?” Source: Vogue.uk.

It’s exhausting to be confronted with the idea that death, in a picture frame, is always a thing of beauty. I kept thinking about this while flipping through Images of Conviction: the construction of visual evidence – Dufour, D. (ed.) – and I kept looking for some reflection on the fact that there is nothing like a “pure documentary approach to photography”. Photography’s aim is always to aestheticize; it has always been. Look at Bertillon’s crime scene photographs and think: how could an exposed brain look so beautiful if the photo’s “purpose” was “only” to serve as proof?

Writing about Bertillon’s metric photographic method, Luce Lebart lets us know that Bertillon was aware of photography’s capacity to trigger emotion, but everything else is “said” by the photographs chosen to illustrate his method. They are described as evidence, as “weapons” in the scientific analysis of crime scenes, but all I can see is how brutal they are and how they make clear that photography lies.

History tells us that Bertillon inaugurated a set of practices related to the use of photography as visual evidence. The methodology applied clearly references scientific experiments. It aims at objectivity; therefore the use of “God’s point of view” is particularly relevant in his metric system. In Bertillon’s crime scene photographs there is no evidence of him wanting to promote something other than the truth, but somehow they remind me of a resource often found in advertisement and propaganda: the pairing of blood and money. One particular add comes to mind: Oliviero Toscani‘s photograph of a bloodstained T-shirt and camouflage pants against a white background, for Benetton (bellow). At the time, Benetton said the uniform belonged to Bosnian Croat Marinko Gagro, killed last July [1994] while fighting Muslims near Mostar in southwest Bosnia. Gagro’s father first was said to have approved the ad, seeing it as part of an anti-war effort. But he later denied the clothes were his son’s, and has threatened to sue Benetton for misrepresentation.

As Henry A. Giroux tells us in Benetton’s “World Without Borders”: Buying Social Change, by hiring Oliviero Toscani (in 1984), the brand was trying to “reinscribe its image within a broader set of political and cultural concerns”. The famous slogan United Colors of Benetton saw its popularity burst in the 90’s and is still a reference when we think of how photography, advertisement and propaganda interact with social reality. As Giroux cleverly notes, “the advertisements render racial conflict completely in this two-dimensional world of make-believe”. Adds such as these fundamentally fail to represent the problem they want to address, but recognizing that implies recognizing one’s place in the hierarchical relations at play. Toscani neved did and his ethical failures are only reflected in Benneton’s success. Its controversial adds made consumers associate their purchases with social responsibility and that is pure gold in marketing strategies.

As controversial as Toscani’s approach to advertising is, he is often thought of as a star. In Aesthetic Journalism: How to Inform Without Informing (2009), Alfredo Cramerotti mentions the expression “creative cheating” to qualify Toscani’s campaigns. He reminds us that Toscani’s intentions were also to unveil the hypocrisy of traditional advertising, which always polarized forces, often pairing glamour with tragedy. But who could believe this?

Fast forward to 2019 and it’s like we’re witnessing it all over again: the branding of social awareness and social responsibility. I would think Toscani and Benneton would have moved on from that leveling strategy that promotes the idea of democracy as simulacrum in a world of make-believe, but guess what? They keep at it. It’s been proven that promoting social responsibility is a great way to sell products, especially in countries of traditional catholic heritage, so why deviate from a formula that has been proven right? Peter Fressola, director of communications in North America, has said that Benetton sponsors “these images in order to change people’s minds and create compassion around social issues”, adding that they embrace it as “art with a social message”. But Giroux quickly points out the overall problem with the brands’ strategy, stating: “Of course, the question at stake here is whose minds Benetton wants to change“.

Toscani shows a black woman nursing a white baby, simplifying the cultural complexities of racism, as if a hug or a kiss could solve all our differences; as if there were no differences at all. But there are, they are culturally engraved and what Toscani’s adds manage to do is to make consumers (used to be in power positions) feel better about others’ disadvantages, as if by seeing standard roles inverted or subverted they were actually experiencing the life of another.

Photography is just another tool when it comes to linguistic discourses. It has its specificities, but they are easily overpowered by words and signs are nothing if not their context. The idea of photography as evidence is not that different from the idea of photography as agent of social change; they both rely on one premise: that there is some sort of universal truth in photography. Well, there isn’t. Photographic images are just as spectacular as any other; its signs as manipulable; they can confirm or deny historical and sociological circumstances but, without context, they make no reference to a collective reality.

As Giroux brilliantly notes, Benetton’s campaigns are exquisite at masking the codes that make them possible and give them meaning: “There is no sense here of how the operations of power inform the construction of social problems depicted in the Benetton adds, nor is there any recognition of the diverse struggles of resistance which attempt to challenge such problems. Within this aestheticization of politics, spectacle foregrounds our fascination with the hyperreal and positions the viewer within a visual moment that simply registers horror and shock without critically responding to it.”

But not everyone is fooled by the color of money. Not everyone is fooled by the Society of the Spectacle. Paul Rutherford (Endless Propaganda: the advertising of public goods) tells the story of how Zapatista subcomandante Marcos refused to play Benetton’s game. In 1996, Marcos received this incredible letter and obviously refused to take place in the charade:

For a long time United Colors of Benetton has chosen to use a large part of its advertising budget to address the most dramatic problems of this century: AIDS, war, racism, intolerance. It’s a way to create a different dialogue with the ‘consumers,’ who for us are first of all ‘men and women.’ We have always chosen to photograph ‘true persons’ – not models – in the places where they actually live. In this way, we have highlighted the beauty of the Chinese, of the Turks, of the inhabitants of a little Italian village, and, recently, of the Palestinians of Gaza.

Today, we address ourselves to you because we sense that you know that communications can be a form of struggle. We ask you to give us an opportunity to photograph you with the men, women, and children of your group, the Zapatista National Liberation Army. We would like to give you a chance to show the beauty of the faces of those who struggle in the name of an idea. We believe that an ideal brightens the eyes and lights up the faces of those who fight to realize it. We do not believe in the beauty myths propagated by consumerism. For this reason, we ask you to receive us among your people and to give us the opportunity to find another way of making your lives and your history known.

As original and successful as Benetton’s shock advertising was, something else made Toscani’s adds influential: their promotion of a lifestyle. Major contemporary brands followed their steps. Just look at Nike’s recent campaign… Evoking Guy Debord‘s thesis of our capitalist society, Rutherford resumes the idea that engaging with reality as if it were “not just a collection of images but a social relationship between people that is mediated by images” marks the triumph of capitalism and the rule of commodities. To escape this rule (and this is me talking) there’s only one option: escape democracy’s simulacrum. Easier said than done, for most people don’t distinguish between commodities and democracy. Referencing Baudrillard, Rutherford concludes: “Baudrillard sometimes emphasized the significance of advertising, which became not just a master discourse but an imperial one as well. For advertising could absorb, translate, and simplify all sorts of content. It had, in short, imposed its form everywhere, on the political and the social. ‘Today, all things … are condemned to publicity, to making themselves believable, to being seen and promoted … ‘ he once wrote. ‘An evil genius of advertising’ had penetrated ‘the very heart of our entire universe of signs,’ its ‘ingenious scriptwriter’ then ‘pulled the world into a phantasmagoria, and we are all its spellbound victims.’ Witness ‘the vicissitudes of propaganda‘”.

Is it possible that Toscani, and other photographers who play the tune of fake-meaning, are themselves dupes? That they want to believe that their work is saving the world, and so they are reasssured while banking the cheque which is the consequence of its ability to sell shoes?