caption: unknown author, at Stockholm Pride Festival

In the past few weeks several events concerning cultural appropriation have motivated public discussions. I’ll be focusing on three: Gucci’s blackface jumper, Amanda Lind‘s dreadlocks and Donata Meirelles birthday photograph with two black women wearing traditional Bahian outfits. The fact that I’m appropriating these events in order to talk about cultural appropriation doesn’t mean I think that’s all they’re about; instead it’s a way to address certain issues related to images and their symbolic significance.

Recently I came across a very interesting article by Teju Cole, for the NYT mag, where the author speaks about a “colonial encounter” that happened after seeing the photograph bellow. Being a Ijebu, from Lagos, Cole explains the meaning of the beaded crown worn by the black man (a Ijebu king – oba) sited right from the white governor (center stage). He says:

The oba wears a beaded crown, but the beads have been parted and his face is visible. This is unusual, for the oba is like a god and must be concealed when in public. The beads over his face, with their interplay of light and shadow, are meant to give him a divine aspect. Why is his face visible in this photograph? Some contravention of customary practice has taken place. The dozens of men seated on the ground in front of him are visibly alarmed. Many have turned their bodies away from the oba, and several are positioned toward the camera, not in order to look at the camera but in order to avoid looking at the exposed radiance of their king.

Reflecting on the photographic medium and its arrival in Africa, in the colonial context, Cole elaborates on imperialism and authoritarianism, associating its violent practices with the way photography (and the visible) imposed itself as a medium that had the power to rewrite history, legitimate certain parts while denying or ignoring others. Cole also suggests that these (violent) practices have survived the 20th century and keep being perpetrated by photojournalists, with the same imperialistic strategy as before. On that note, he adds:

Certain images underscore an unbridgeable gap and a never-to-be-toppled hierarchy. When a group of people is judged to be “foreign,” it becomes far more likely that news organizations will run, for the consumption of their audiences, explicit, disturbing photographs of members of that group: starving children or bullet-riddled bodies. Meanwhile, the injury and degradation of those with whom readers perceive a kinship — a judgment often based on racial sympathy and class loyalties — is routinely treated in more circumspect fashion. This has hardly changed since Susan Sontag made the same observation in “Regarding the Pain of Others” (2003), and it has hardly changed because the underlying political relationships between dominant and subject societies have hardly changed.

[…]

Photography’s future will be much like its past. It will largely continue to illustrate, without condemning, how the powerful dominate the less powerful. It will bring the “news” and continue to support the idea that doing so — collecting the lives of others for the consumption of “us” — is a natural right.

Cultural appropriation is a very curious subject.

On the one hand, appropriating cultures that are foreigner to us seems strange and, in a way, offensive, since that gesture trivializes and denies its symbolic significance. Cultural appropriation is a popular strategy; it massifies something – in order to talk about its mundane and finite qualities – and questions the spiritual value of material culture. It questions fetishism, while turning something into a fetish. It’s almost genius.

On the other hand, cultural appropriation tends to be criticized by people who use arguments that, at their core, are against what they are trying to defend. What happens is that when we criticize cultural appropriation we tend to defend a set of values that praises cultural traditions, national identity, collective identification, etc. and these slogans are very dangerous. Moreover, these values tend to be defended by people who are perpetrating the very same hierarchic structuring of society that they oppose to.

Should I, a white european born in the 80’s (to white caucasian parents), be defending the rights of indigenous people whom I have never met? Should I defend “their right” to be the single users of feathery headbands? It sounds inappropriate.

In an article from 2015, Cathy Young addressed the growing accusations of cultural appropriation, suggesting that the problem is that the public levels everything, failing to address what’s at stage in different situations. As she tells us, “[t]he concept of cultural appropriation emerged in academia in the late 1970s and 1980s as part of the scholarly critique of colonialism.” The “anti-appropriation rhetoric”, as she describes it, is born out of a very specific sociological context in which the colonial relationships play a large role. In past times, condemning cultural appropriation is deeply associated to the condemnation of violent relationships between those with power (and purchase money) and those with survival needs.

Like Young, most scholars associate cultural appropriation with an anti-capitalist rhetoric, but there’s obviously more to it, since popularizing cultural symbols often promotes the denial of history and that, I think, is a serious issue. Regarding the dangers of applying an extremist rhetoric to this issue, Young concludes: “In some social-justice quarters, the demonization of ‘appropriative’ interests converges with ultra-reactionary ideas about racial and cultural purity.”

So let’s look at some recent examples.

I

Gucci’s blackface

Anyone with a basic visual culture recognizes this is offensive. Even if you don’t have a clue about the meaning of a “blackface”, you should recognize this promotes a culture (by replicating, without any critical intentions) that makes caricatures out of those it despises. No doubt at Gucci they knew what they were doing, so why pursue it? Well, basically because this appeals to their public – white people with money (who need material possessions to assert them of their purpose in life). Let’s not forget the “balaclava knit top black” was priced at $890. Regarding this example, I feel there’s no need to bring up a discussion between what constitutes cultural appropriation and what is the promotion of a worldwide cultural inheritance. Facing accusations of racism, Gucci took the product off the market and that’s the end of the commotion. The fashion market will go on making fun of human’s violent relationships.

II

Amanda Lind’s dreadlocks

Since January 21st, Amanda Lind has been part of the Swedish Government, working as a Minister of Culture and Democracy, with responsibility for sport. Because her hairstyle is not ordinary in the context of such a profession, no time was wasted before accusations started to assault her, regarding her looks. For the case, the quality of role she plays as a politician is not relevant; no conclusion from that would participate on this argument about the way she presents herself. So what’s the problem here? None, or several…

Here are some reactions:

On Twitter, right-wing polemist Rebecca Weidmo Uvell was one of the first to react, making sure she did not have the habit of commenting on people’s physiques. “Except that as a minister you do not represent yourself. But Sweden. Especially in an international context. And I do not think we can have such a hairstyle. ”

Since then, the discussion has taken a new turn. With her dreadlocks, Amanda Lind is accused of cultural appropriation. In a tribune of the Aftonbladet newspaper, Nisrit Ghebil, a young artist and black communicator, called the minister insinuating that a white woman, in a position of power that is more, “should not wear an African-American hairstyle”, especially when young blacks, in the United States, for example, continue to be expelled from their schools for coming with the same cup.

Source: https://www.lemonde.fr/m-le-mag/article/2019/02/08/en-suede-les-dreadlocks-d-une-ministre-defrisent-la-chronique_5421076_4500055.html

I don’t think this particular situation brings anything new to the discussion about cultural appropriation, apart from the fact that she is a politician in the midst of a continent that is leaning towards right-wing ideologies. That, and the fact that reactions to photographs in the social media trigger irascible decisions, creates the illusion that this is news, but it isn’t. Does that mean we should dismiss it altogether? Maybe not.

I had a conversation about this with my students and the first question I faced was quite difficult to answer. Regarding the critics about the minister wearing a Rastafarian look and it being cultural appropriation, one student asked: Doesn’t that approach condition our freedom? At the time, I tried to create some scenarios where appropriation had different symbolic meaning (and thus impact), to promote critical awareness and pay some respect to the history of violence, in particular. Now, when I think back on the student’s question, I actually stop at the word “freedom”: what does the equation of fashion with “freedom” entail? When students consider their “freedom” to dress or look a certain way, should one address the cultural implications of fashion?

I’m one to critique others for wearing dreadlocks (if they’re unaware of Rastafarian culture), as I critique people for wearing t-shirts with symbols or names they know nothing about. It’s a critique of ignorance; fashion appropriates our cultural landscape and transforms it into a trend. Dreadlocks are symbolic in Rastafarian culture, but Ramones are as well to music and punk-rock culture. Is one more important than the other? That’s really not the point. The question here is: aren’t these symbols (and their cultural significance) bigger than their material history? If they have such a significance, aren’t they part of a spiritual dimension? So why do we react to the commodification of the symbols that are dear to us? Is it an emotional reaction concerning the way we structure our notions about identity?

III

Ms. Meirelles and our colonial past

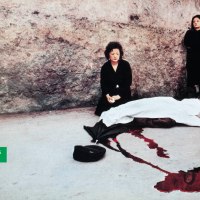

Donata Meirelles was Vogue Brazil’s Fashion Director until this week. She resigned after publishing a photograph commemorating her 50th birthday. The accusations were that she was promoting the racist paradigm (which implies slavery relations). Again, like on the Gucci case, it seems obvious to me that this image is a perfect example of how racism is still intrinsically rooted in our societies. Ale Santos, on the issue, makes a brief statement about racism. It reads: “Contrary to what is common sense, racism is not just racial insult, when there is direct offense or supremacist action that will demean the presence of an Afro-Brazilian. That is the tip of the iceberg, it is the moment in which the whole structure of thought gains strength before a social condition materializing its prejudice.”

Slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, soon after the same had happened in Portugal. To this day, that disposable relationship between white and black people is evident in our societies. Black men and women are often treated as commodities; that’s particularly evident in trading contexts. Fashion and agriculture are just two of the dimensions where racism and slavery still play a huge role, but since our democracies are capital driven, this commodification can be seen anywhere.

“Ana Lucia Araujo, a history professor at Howard University who studies slavery“, said “the mere presence of women dressed in the traditional baiana outfit of white blouse, skirt, headwrap and beads should not be construed as racist” and maybe that’s an accurate statement. On the other hand, these women weren’t dressed like this because they wanted to celebrate their cultural inheritance. The context in which they appeared in such vests in of the uttermost relevance here. One should also add that these women, proudly dressed in their traditional costumes, have said they were there out of their own will. So what should we think of this? Is this about these women’s dignity? No, it isn’t. In fact, they’re paying a very poor tribute to the human race and our violent history by putting themselves in that situation. Oh, but they need to make a living. Of course, they do. I do to. The question concerns critical awareness and not financial power. If my symbolic representation is irrelevant to the way I make my choices, I won’t have a hard time playing certain roles.

Anna Kaiser writes that “[c]ritics compared the women’s clothes to the white uniforms worn by house slaves, and pointed out the chair’s similarity to a cadeira de sinhá, an ornate chair for slave masters.” In fact, the similarities between the symbolism evoked in Meirelles photograph and images that are part of our visual culture, are more than many. One can claim the presence of the baiana tradition is an homage and nothing more but that has to be one of two: either dishonesty or ignorance. Dressing black people in white clothes is an habit deeply rooted in colonial practices. The white gloves, worn by black waiters, are the epitome of that. I’m thinking of a scene from “Out-of-Africa”, near the end, when Farah appears wearing white gloves and Karen tells him it was a bad idea… that movie is rich in colonial imagery; a true lesson in history.

But there are other symbolic signs at play in Meirelles’ photograph. For instances, the fact that she is sitting and the “other women” are standing. Yes, she has other pictures where they are all on the same level, but the thing is she chose this one; the one where her (un)conscious understanding of power is displayed. Racism towards the black community is something very difficult to address, because it is a very complex issue. A lot of black women have felt that they add to adapt to other’s culture in order to be accepted. Some straighten their hairs for instance and it’s understandable that other female black activists find that offensive. I find offensive a lot of things that my pairs do. At the end of the day what matters is that we distinguish between those who aim at promoting hierarchical relations of power and those who get caught in that structuring, knowing or unknowingly. Critical awareness is massive here. Extremist groups excel at appropriating silent rhetoric to manipulate audiences and it’s in everyone’s hands to prevent the denial of history.