I’ve got a ton of shit to do and a multitude of voices controlling my every thought, writing stories that will one day be told, but not now. The only match I can seam to operate today, between what’s going on between the public and the private sphere, is to write, once again, about war imagery and propaganda. Yes, once again, rage, rage and more rage.

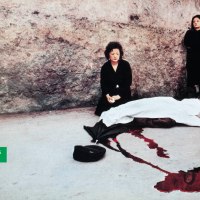

As many of you, today I woke up to the images of the Bucha (Буча) massacre (warning: truly disturbing images). Maybe I fell asleep to them, can’t tell. Watched the news, read a couple of articles, cried, then stumbled upon Publico‘s digital edition (image above) and threw up in my mouth. Not because the image is exposing some horrible reality that is making me sick, but because its framing, in the context it is shown, is beyond unethical. Made a printscreen, saved it to a folder crowded with similar stuff and then went on with my day, guarded by the saving sounds of metal.

While we close our eyes and lean our heads on soft pillows, war in Ukraine unfoldes and, just like any other war, news of gruesome massacres start to circulate. We hear about Bucha and remember similar events in war history (or at least I do), but fail to understand our place as witnesses.

While photographers and writers, like Jörg Colberg for example, keep reviewing the interplay of images from the war in Ukraine, traditional media (mostly newspapers and TV channels, for the case here) keep using photographic imagery as if they were cartoons. Don’t get me wrong, I’d rather see cartoons, have little doubt it would be much more educative to appeal to the empathetic imaginarium of drawing under the circumstances, instead of using photographic imagery showing parts of bodies to illustrate the idea that war is killing civilians. That arm has a body, that body is an individual whose shattered life guaranteed the loss of that individuality. That individual being has a name. It’s a fucking person. See, photographs made with cameras have this complex framing: for once, they maintain a physicochemical relation to the events unfolding in the lens’ field of view, inscribing traces of “real life”, in a temporal and spatial dimension that we recognize as common to an humane perspective; on the other hand, before they can represent that “humane perspective”, they are already fictional imagery, simulacrums, symbolic construction, evoking iconography and cultural paradigms. So when someone reading the paper sees an image of a chopped arm, that arm is deprived of its temporal and spacial circumstances, its humane perspective, and thrown into the vast void of signs: a chopped arm, as trace of death, pain, suffering, war; as trace of a fallen body, a chopped life. The humane perspective would have to include the naming of the person whose chopped arm is being showed. Of course, it may be impossible to identify the person, but that’s not the point just yet. Why make this photograph and throw it into the massive void of stock imagery? But maybe that’s not even what needs to be questioned here. What is it then?

Let me tell you: I’d like to name the fucking person – at Publico – responsible for choosing to do this. Albeit it’s not a humane perspective, it is most definitely a human choice. So who is he or she? The editor? The person responsible for what they call “digital design”? As I upload the image to google to try and trace its origin, here’s what happens: google identifies it as a symbol of “blood” and regurgitates a gallery of chopped body parts. Very enlightening indeed to the point I was trying to make about the referent in this image – the person – being made redundant, irrelevant, given its iconic nature.

Yeah, yeah, yeah, these people in the newspaper are just replicating what every other news outlet is doing. Read that out loud and then think if this is really the sort of argument anyone should be making here. I’d like to suggest you go a bit further and call people on their complacency if they choose to keep putting this off as “normal”.

I finally traced the origin of the image to Zohra Bensemra (though allcrimea.net identifies this as the author). I see it in a video, but also as a photograph with a caption that reads: The body of a woman who local residents say was killed by Russian army soldiers lies on the street in Bucha. The caption fits with what is showed in the video (here, beware, difficult to watch), but it is already appearing in several others sites as just another image “illustrative of blood”. In all of the sites I found the image, only two identified the photographer. Some sites used the image to illustrate the news that account for proof that Russian soldiers are raping women, and then there’s stuff like the one bellow, proving my point, and not even a day has gone by.

We need to be naming names. Of course of victims, every single time it’s possible, but also of murderers and abusers. I can understand the photographer making this image. Don’t like it, question its ethics, but can empathize with the situation and can believe the photographer did not intent to impose further abuse on the victim. On the other hand, editors, “digital content designers” and what the fuck not, are to blame. They are abusers if they take the image out-of-context and use it as a symbol, as a featured image. Yes, if Zohra Bensemra didn’t send the image, that abuse would not happen. It’s a fact. In the case of the news about this particular massacre, I think the argument of it being necessary to expose atrocity is in place, that’s why we’re seeing all sorts of unimaginable portraits of men and women executed. Might this be a case (I’m reminded of another one) where shooting “traces of blood” is not respectful to the violent nature of the event?