photo caption (above) © Katie Innamorato, Coyote Terrarium, Coyote skin, foam, LEDs, clay, moss, glass, plastic, 9vt battery

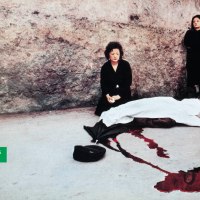

This photograph by Caroline Tisdall is from Joseph Beuys: Coyote, a 1976 book documenting Joseph Beuys’ 1974 performance art piece, Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me, in which the artist spent three days and nights caged with a wild coyote in René Block’s New York Gallery.

This photograph by Caroline Tisdall is from Joseph Beuys: Coyote, a 1976 book documenting Joseph Beuys’ 1974 performance art piece, Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me, in which the artist spent three days and nights caged with a wild coyote in René Block’s New York Gallery.

© Frederick Sommer, Coyotes, 1941

© Frederick Sommer, Coyotes, 1941

© Frederick Sommer, Coyotes, 1941

© Frederick Sommer, Coyotes, 1941

“The ritual, obsessional, and quasi-exhaustive character of this list of the roles he either assumed or impersonated (lacking – and this is significant – only that of worker and prostitute) sets up echoes between Beuys’s work and an already extensive litany of similar identifications, all of them allegorical of the condition of the artist within modernity, all of them leading directly – more than a century distant – to a mythical country peopled with all the romantic incarna-tions of the excluded as bearers of social truth.

(…)

Doubtlessly, the real name of bohemia is the lumpenproletariat, or at least, the name of its correlate within the actual world: a no-man’s land into which there fell a certain number of people incapable of finding a place within the new social divisions- expropriated farmers, out-of-work craftsmen, penniless aristocrats, country girls forced into prostitution. Dickens and Zola have described this dark fringe of industrialization, these shady interstices of urbanization. But, like Baudelaire, Hugo, and many other novelists who hardly professed naturalism, they poured their inspiration into it, contributing to the fabrication of the image of this marginal, lumpenproletariat society transposed into bohemia, functioning all the more as the figure of a humanity of replacement in that it is a suffering humanity, such that nothing but true human values–liberty, justice, compassion–can survive there, and such that it contains the seeds of a promise of reconciliation.

(…)

The proletarian – a term that transcodes the bohemian as a social type that excludes the bourgeois but includes all the rest of humanity suffering from indus-trial capitalism – is not (or not necessarily) a member of the proletariat, that is, the working class. Of this latter, the myth of bohemia offers a displaced and transposed image; it creates of a transnational reality an imaginary land, a quasi-nation, without real territorial frontiers, since it is peopled with nomads and gypsies, unreal, like Jarry’s Poland. The worker himself is rarely an inhabitant. The image of bohemia, one could say, is ideological to the extent that it occults the reality that it is precisely charged with transposing: the massive proletarianization of all the men and women who did not belong to the bourgeoisie. But the proletarian is a construction no less ideological – or mythical – of the same personage or social type that the bohemian expresses in the discourse of art and of literature. Simply, it expresses it in the discourse of political economy, that of Marx, and even more specifically, of the young Marx. What, then, is a proletarian for Marx? He is someone-no matter who -who finds himself to have everything to lose from the capitalist regime and everything to gain from its overthrow. Everything to lose-which is to say, his very humanity–and everything to gain – this same humanity. The proletarian is, then, from the origins of industrial capitalism, a figure torn from the future horizon of his own disappearance. He is literally the prototype of the universal man of the future, the anticipated type of the free and autonomous man, of the emancipated man, of the man who will have fully realized his human essence. This essence lies in the two things that define man ontologically, as both a productive being and a social being. He is also a historical being. But as historical changes are only conceivable against the ground of an invariant substrate, they postulate an ontology, and the history of men can be nothing but the growth of productive forces and the progress of the relations of production. For Marx only conceives of man as homofaber: labor – the faculty of producing – is what makes him man, and the consciousness he has of it is the import of his humanity. It transforms the simple biological belonging to the human species into conscious- ness of participating in humankind, and thus makes of all products of labor the privileged place of collective living. This is why the social relation is the essence of the individual as Gattungswesen (species-being), and why as well, in turn, all social relations are, in the last instance, reduced to relations of production. These latter will only be free and autonomous with the advent of the classless and stateless society, the communist society of which the proletariat is the avant- garde. In the meantime the class struggle will be the order, since the proletariat is exploited and alienated by the capitalist regime to which it is subjected, or, to put it another way, since the proletarian, dispossessed of his human essence by social relations of production which admit of nothing but the regime of private prop- erty, still needs to reappropriate it through struggle.

(…)

But subjectively speaking the modern artist is the proletarian par excellence, because the regime of private property forces him to place on the art market things which will be treated as commodities, but which, in order to have an aesthetic value, must be productions and concretions of his labor power and, if possible, of nothing else. (…) Marx calls this universal faculty of producing value labor power; Beuys calls it creativity. Beuys is certainly not the first to give it this name, far from it. He is more like the last to be able to do it with conviction. Beuys’s art, his discourse, his attitude, and above all the two faces presented by his persona-the suffering face and the utopian face–constitute the swan song of creativity, the most powerful of the modern myths.

(…)

“Everyone is an artist.” Rimbaud already said it and Novalis already thought it long ago. The students of 1968, in Paris, in California, and gathered around Beuys in Dusseldorf, proclaimed it once again and wrote it on the walls. It always meant, and this since the German romantics: “power to the imagination.” It has never become a reality, at least not in that sense. But all that the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have implied for the will to emancipation and the desire for dis-alienation has always meant: everyone is an artist, but the masses don’t have the power to actualize this potential because they are oppressed, alienated and exploited; only those few, whom we stupidly call professional artists, know that in reality their vocation is to incarnate this unactualized potential. Hence the two faces of modernity, of which it is Beuys’s pathetic grandeur to have worn both: the public, revolutionary, and pedagogical face, the one that is convinced that an adequate teaching will liberate creativity; and the secret, insane, and rebellious face, the one that claims that creativity is already of this world precisely there where it lies fallow and in waiting, crude and savage: in the art of madmen, children, and primitive.”

excerpt of Joseph Beuys‘, or The Last of the Proletarians, by Thierry de Duve in October, Vol. 45