This is not one of my usual posts. In conversation with Rotem Rozental, the editor of the Shpilman Institute for Photography blog, she suggested I should take a look at a couple of her posts and that’s how I came to encounter Yaron Lapid‘s work. Featured here is Rotem’s conversation with him, along with images from his work.

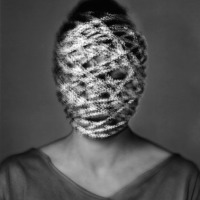

© Yaron Lapid, Not only England, but every Englishman (is an island), from Original stories from real life

© Yaron Lapid, Not only England, but every Englishman (is an island), from Original stories from real life

Rotem Rozental: Let’s start where our last meeting ended: it was in Jerusalem, and you talked about the reason for you being there and how the experience of returning to the city affected you. Can you describe what you were doing there and share that experience?

I also wonder how this complexity became an active participant in your work. It seems Jerusalem and her conflicts influenced your works at various junctures. You began your career as an artist there, as a student in Bezalel Academy. I’m wondering if this complex city became an active participant in your work and how your first years there influenced your critical approach?

Yaron Lapid: We met in Jerusalem last, and you would be right in saying the mixture of extremes in the city fascinates me. Perhaps it has to do with my biography. I grew up in a religious family, although I had a strong science-based education, with all the inherent contradictions that entails. I went on to travel in South-East Asia for three years. On my return Jerusalem was the only place that could offer the complexity I sought.

As a former religious boy with an interest in science, nothing was further from my thoughts than the arts, except literature. This might be why it was easier for me to pick up a camera, which I first did to try and capture my experiences. I stumbled upon the art world and found that it allowed me to engage in storytelling, which is a central element in my practice. Some of my works could be considered a piece of a story, like You Have not Found his Riddle and, I think in all my works, even the more abstract ones, a narrative is implied through the connections I create.

Jerusalem was, of course, full of stories. I lived there for six years including the mad times just before the Millennium, when the city was buzzing with religious highs and anxieties that permeated down to street level. Night Meter is a work from the end of 1999, made as a response to that time.

© Yaron Lapid, still from the video work You Have Not Found His Riddle (left); still from the video work Night Meter (right)

© Yaron Lapid, still from the video work You Have Not Found His Riddle (left); still from the video work Night Meter (right)

I also lived in Jerusalem during the bloody years of 2001-2003, where as students we were either doing blatantly political work, or work that was completely escapist. I have always felt the need to deal with what is directly in front of me, but I felt that “the conflict” was molded in such a finite way. I didn’t want to limit myself to the immediate political situation but rather was interested in the broader human landscape, which inevitably includes political content. The more conceptual type of work interested me less; I wanted to make work that one has to experience with its value rooted in the finished piece, not only in the artistic idea.

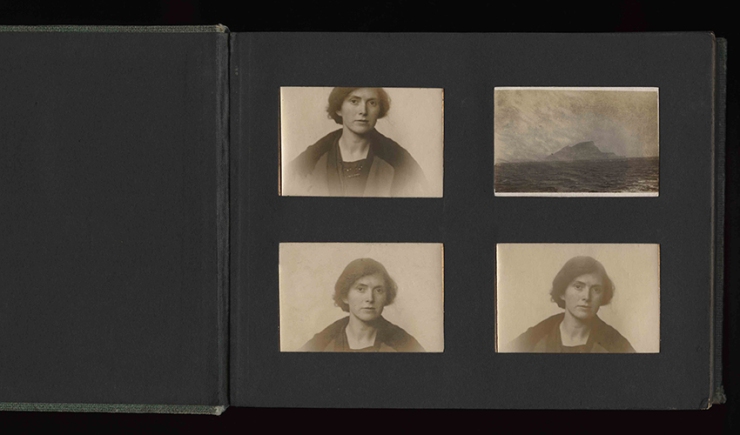

RR: To continue with the theme of context and location, let’s discuss the project The New Zero. Ayesha Hameed writes about the alternative documentation of the city that these found images might suggest to you and the viewer. I was wondering about your role here, first as the collector of the images and then as archivist: utilizing technology to intervene in private, lost histories, while manipulating the images themselves.

YL: In part, The New Zero was created as a response to the impossible contradiction that Jerusalem signifies for me. The piece satisfies my attraction to the found, the abandoned and the cast aside. The images are simple yet beautiful and touching, and in my interference I tried to echo the frustration and fascination of living in Jerusalem at the time: a place where history is unfolding before your eyes.

© Yaron Lapid, from The New Zero

© Yaron Lapid, from The New Zero

Although my website is called Finder & Keeper, I am of course also a manipulator. I see the documentary as an art form, through which an aspect of reality is conveyed, but like Werner Herzog says, facts per se do not constitute truth, otherwise the Manhattan phone directory would be the book of books.

Francis Bacon says “You can see an advertisement, you can see something lying in the street.” I see people lying in the street, but also advertisements interest me as an artist, in an attempt to figure and mediate reality. I would like to reflect an inner truth, one that doesn’t rely upon the surface, yet is connected to quotidian reality.

RR: How did your interest in English family archives develop and how do you approach such intimate, private material?

YL: History is a slippery process, which is hard to pin down in the present. The photographic archive is a great source of visual knowledge, although I am not interested in nostalgia, but rather the similarities and differences between times, and the reasons and effects of that. It is not only images I find and use; other human footprints could be utilized to reveal something about a time, a place and a person. Full. Stop. is made of two flyers found in the streets of my neighborhood, and is titled after the anonymous writer’s preference with punctuation.

RR: So now your work is in constant dialogue with and is invested in a very different urbanscape, which necessitates a different viewpoint. I was wondering about the relationship between your status as an immigrant in London and an artist in a new surrounding, and your critical view of that surrounding as it is conveyed in your work. I am thinking, for instance, about your exhibition at Alfred Gallery in Tel Aviv, where these works, in a sense, also “immigrated” out of their original context.

YL: Living in London has changed both my life and my practice. I see parallels between photography and being an immigrant. A photographer is a person who distances him or herself by using the lens as medium, like Perlov’s soup dilemma – to eat it or to film it. In that sense, a photographer is somewhat of an immigrant: half here, half existing a different context – through the prism of another culture or through the edit.

London is not an easy place for an immigrant, especially not an Israeli one. I am not like any other “ethnic minority” in this cosmopolitan city. Some regard Israel, with some justification, as a problematic country, although often their understanding of the situation is poor.

Some of this is reflected in the Alfred show which was centered on family. The family I see in London is quite different to the one I know from Israel. The show was composed of works I found as part of my research, when I started working with found photos from Britain. My interest in images of British lives also derives from the insight it gave me into family moments, in a society where separation between inside and out is very present. One of the resulting works is Partial moments from which the SIP image is taken.

© Yaron Lapid, from Partial Moments

© Yaron Lapid, from Partial Moments

[…]

RR: Your camera also finds its way to other private spheres. I was surprised by the intimate nature of your work in the series Dad and I taking each other after Mum Died. Beyond the traumatic experience, the physical comparison between yours and your father’s bodies (the naked torsos, the beards) is striking. The two of you seem to be unified by pain, limited by it and by the dense physicality of the neutral space. However, you were also divided as soon as each of you assumed the photographer’s position, documenting the other.

YL: Yes, this is probably my most personal work to date, and the mental process you have gone through is the one I hoped for. On top of the raw emotions in the images and the reference to my mother’s death, I was also considering the nature of photography: how we look at someone when we take a picture, never the same as someone else will, and really never the same as we have looked at them at any other time before.

© Yaron Lapid, from Dad and I taking each other after Mum Died

© Yaron Lapid, from Dad and I taking each other after Mum Died

[…]

RR: What is your next project? What are you working on now?

YL: I am working with footage I shot in Jerusalem, which will hopefully become a movie. I must admit I am a bad artist, in that I do not work as a trained professional is expected to work. At any given moment I have up to ten projects I am playing with. Every now and then – usually late at night – something falls into place and a project gets nearer to completion.

In art school one talks about research subjects as a result of critical thinking, but this is not the case for me. Instead, I would describe my process as finding a set of connections by doing what I need to do, and then gradually, the theoretical framework surfaces. I create work because something draws my attention, and I think about it critically because that is inevitable. Although I am conscious of the critical aspect of my work, what ultimately pushes me to make it is curiosity.

© Yaron Lapid, from Signal Failures

© Yaron Lapid, from Signal Failures