Jörg Colberg, from Conscientious Mag, wrote an essay on the need for subversive photography that can be found on Hyperallergic. As Colberg reflects on what subversion “looks like”, he starts by comparing two photographs: Time´s cover portrait of Trump, by Nadav Kander (2016), and Jill Greenberg’s cover portrait of John McCain, for the Atlantic (2008). For Colberg, comparing these approaches by such different authors makes clear that Trump’s portrait by Kander is not subversive AT ALL (Time’s placement of the lettering is a different question). I couldn’t agree more. If one looks at Greenberg’s complementary photographs from that session with McCain there’s no doubt that she’s committed to being transgressive and original. Can an author be subversive if he/she insists on not committing to anything deemed political?

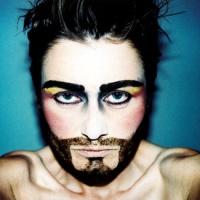

Regarding Greenberg’s photographs, Colberg emphasis falls on her use of the back lightning and how that shadow has symbolic meanings (the horror movies to start with), for she chosed to highlight how menacing McCain is. To sum up the history of how Greenberg got these photographs, she tricked the Republican presidential nominee into standing over an unflattering strobe light, then posted the worst shots and Photoshops to her personal site. The magazine then said the author had disgraced herself. Curiously enough, Colberg had a different opinion back in 2008, when the manipulated photos of McCain by Greenberg came out, calling Greenberg’s actions […] simply incredibly disgraceful and unacceptable. I guess the problem is that we need subversive art, but then it apparently fails to comprise with our moral standards. But a subversive action is never to be received without some uneasiness, some rejection. Otherwise, if it din’t question what we take as granted – be it our values, rights or beliefs – how and why would it be considered subversive?

I find it refreshing when people change their minds, as seems to be the case in this Colberg vs Greenberg episode. These were his words back then: Frankly, I’m still baffled how Jill Greenberg could even think that her actions were in any sense a meaningful political statement that would be taken seriously. It’s mind-blowing. It degrades political discourse to levels that even the worst cases of political mud throwing thankfully only rarely reach. As I see it, what Colberg failed to understand back in 2008 is that Greenberg isn’t bound by the same rules that apply to politics and journalism and her biggest compromise is to her work, not the magazine or its readers. She took the opportunity to make subversive imagery that apparently offended people’s ethical standards, but she suffered the consequences. 9 years later, here’s what Colberg has to say about the McCain portraits: Say whatever you want about the pictures Greenberg produced; whether you like them or not, aren’t they subversive? Isn’t lighting a politician from below, to make him look menacing — and not at all palatable to a magazine’s readership — subversive?

Resistance is one thing, but being subversive is something entirely different. I guess the times we’re living are so challenging that now the act of resistance is radical enough, polemical enough. Just see the discussions around the way some people decided to protest agains Milos Yiannopoulos conference at Berkeley. Apparently, in light of free speech banner we should all simply stay put while white supremacists promote their way of thinking. Don’t the people who protested, “those 150 masked agitators” (as reported), have the same rights than the guest whose ideals they vehemently oppose. I’m aware their methods is what shocks people, but would it be that different if the conference had been cancelled because of a pacific protest? Maybe trowing Molotov cocktails and smashing windows is by some considered a subversive attitude, because if defies the law and the way most people resort to protest, but it lacks originality and doesn’t have a transformative goal in mind, so how can we consider it a political act?

Consider the latest Der Spiegel conver, an illustration by Edel Rodriguez depicting Trump beheading the statue of liberty. We can all agree it is controversial, but is it subversive? And, whatever we may call it, is it because the illustration is shown in the cover of a magazine or is it the artwork controversial in itself? According to Hal Foster (in RECODINGS: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics, 1985) some political art entail the sort of compromise that is merely presentational, failing to give expression to the critical stance that is inherent to political art. In Foster’s view, this critical character should have two type of manifestation: one that is transgressive and aims to transform; another that resists aims to question the normative systems of production. If political art fails to do either, than it also fails its critical function, instead promoting the same mechanisms of production that it should be question and/or transforming. As Foster concludes:

“Presentational political art, then, remains problematic. And this is so, above all, because such art tends to represent social practices as a matter of iconic ideals. However general the social practices of the industrial worker are, as soon as they are represented as universal or even uniform, such representations become ahistorical and thus ideological. It is here that the rhetoricity of presentational political art is exposed: for when such art seeks most directly to engage the real, it most clearly entertains rhetorical figures for it. In the west today there can be no simple representation of reality, history, politics, society: they can only be constituted textually; otherwise one merely reiterates ideological representations of them. Generic political art often falls into this fallacy of a true or positive image, and from there it is but a short step to an axiological mode of political art in which naming and judging become one. Politics is thus reduced to ethics — to idolatry or iconoclasm — and art to ideology pure and simple, not its critique.” (p. 155)

Some called Rodriguez’s illustration “tasteless”, others said it “devalues journalism”, but what we all acknowledge is exactly what the author was putting forward: the idea that the the values promoted by ISIS and by Trump’s administration are not that different, both have zero respect for human lives, both promote hate and both are willing to do whatever is necessary to attain their goals. Is that a subversive statement? I don’t think so, those comparisons are not only obvious but they promote the sort of rhetoric that devalue the history that brought us to this point. If something is controversial here is the fact that it is featured in the cover of a well known magazine, but is that enough to make it a transgressive political work of art?