If there’s one thing different kinds of feminism can agree upon is their will to “empower women”. But, that’s it; once we get started on the meaning of that “empowerment” the apparent cohesion starts to fall apart.

Some co-called feminists think about themselves in such a way because they applaud and promote women’s confidence towards their body. Maybe these so-called feminists go so far as to actively participate in helping certain women feel good “in their own skin”. I can see the importance of this, of course. No man will ever understand what it is to grow up surrounded by beauty stereotypes and how much it can impact your self-esteem – it’s the models in the magazines, the actresses on film, the pop stars and the barbie look, the tv hostesses, the female porn actresses and their big breasts. It’s overwhelming. Some people will consider that empowering women by helping them feel beautiful and sexy is to be a feminist. And, yes, I disagree 100%. I guess what makes this question so problematic is that one easily looses sight of what the feminist struggle is about and although it can be a lot of different things, what it must definitely is not is an individualist struggle that promotes cliches about the importance of owning one’s own sexuality. Feminism is always about the collective. It really can’t be any different. We fight for equality and my victories and losses will have a direct impact on other women and vice-versa.

Feminism is about inclusion, about gaining back women’s parity (yes, in the so called primitive era things were different, and not everything was worst). For that and many other reasons, in its core to be a feminist is to be anti-capitalist, for, in itself, capitalism promotes an economic treatment of everything and everyone and we know how women rank in that economy… (my) Feminism starts by questioning the dynamics of a society that is built upon a patriarchy. Classes, in such a society, will only survive if women continue to agree to be part of a specific sexual dynamic, namely a monogamist one, in which the man is usually the owner (of land and so forth). It’s understandable that these so-called feminist movements who empower women by helping them feel sexy forget that the very idea of what constitutes “sexy” is the doing of men: men who are stylists, men who work in advertisement, men who are writers, men who are directors, men who are photographers, etc. For many years these men have been responsible for objectifying women’s bodies, to a point that women now fail to understand what that objectification is like. One argument is recurrent in this discussion, namely that if women are in control of their body, one shouldn’t speak about objectification, but empowerment. I’m surprised how we still fall for such a false debate, for the question is definitely more complicated. How can one judge other’s information, knowledge, awareness or conscious in order to decide whether they are or are not in control of their bodies? And how do we then deal with sexual abuse if the “victim” is under-aged and willingly goes to her abuser? Recently, in Portugal, I came across a story in the newspaper about a 13 year old girl who went missing from her family for a week and was then found in a house with a sexual offender. They apparently met online, he seduced her and she went to him. He had done that before, meaning he has already abused young women. What is chocking in this story is that 99% of the online trolls were saying that this man had committed no crime, for she went to him of “her own free will”, because young girls “are not as naive as we think”, because “they know what they’re doing”. See the problem?

We could talk about Hollywood, how Scorsese has a lifetime of denigrating women on screen and still everyone loves him; or how the entertainment community legitimates sexual harassment, but what I think could help shine a light on this dilemma is if we consider the roles some women have been playing on screen and how off screen they consider themselves to be feminists, in the context of that very same idea of empowerment we were talking about – because they’re independent, they’re successful, they’re comfortable in their bodies and in control of their sexuality so on. If a female actress spends her years giving life to characters who are treated as objects in a men’s world, could we really consider such actress to be a feminist in her off-screen life? It’s not a tricky question, the answer is a clear no. The promotion of such dynamics between men and women not only legitimate the sort of abusive relations that describe this era of capitalism, but they also infect visual culture in a very profound way. In fact, one shouldn’t be surprised if a younger generation who only watches american entertainment (be it movies or tv series) had a completely distorted notion about what sex is like. For americans, apparently, it’s about 1 minute in bed and the man reaching an orgasm. The consequences of such a misogynist representation of sexual intimacy is unimaginable. Hopefully they’re still watching some “good porn”.

Often, when one discusses “the empowerment of women” one also comes across expressions such as “strong” and/or “fearless“. What these adjectives hide is that in the process of becoming “strong” and “fearless” one usually compromises one’s own femininity, in order to “be more like a man”, but with a skirt and preferably wearing high heels. There’s even a page on facebook called “Project strong Woman”. As expected, it is about empowering women to become their better selves and then go out and celebrate.

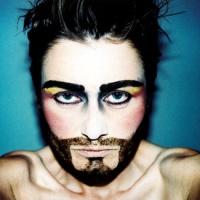

To avoid becoming any more cynical, here’s a photographic approach that challenges the very idea of “the male gaze”.